When it comes to language learning, I lately prefer to jump straight into reading, with just a cursory look at the grammar, and to figure things out from the context.

It’s more fun this way, and maybe it’s also the fastest way to learn.

When you’re forced to figure things out from the context, just like with immersion, you retain that knowledge much better. You’re also sending a clear signal to your brain that you need to learn this language, for real.

I thought I’d take you behind the scenes and show you what this reading process looks like. Hopefully, it will inspire some of you and won’t be too confusing to the rest of you.

Mindset is everything

I’m not usually a glass-half-full person. I wake up every morning convinced that I haven’t accomplished enough the previous day, that I’ll never amount to anything, and that daily existence is generally a hard and thankless job. I have to work hard to muster enough optimism to get me through the day.

But when I see a paragraph in a foreign language and don’t have a clue what it is about, I become a fountain of confidence and optimism. I don’t know where it comes from but I’m pretty sure that’s my superpower. Not so much the ability to quickly figure out grammatical patterns but mindset.1

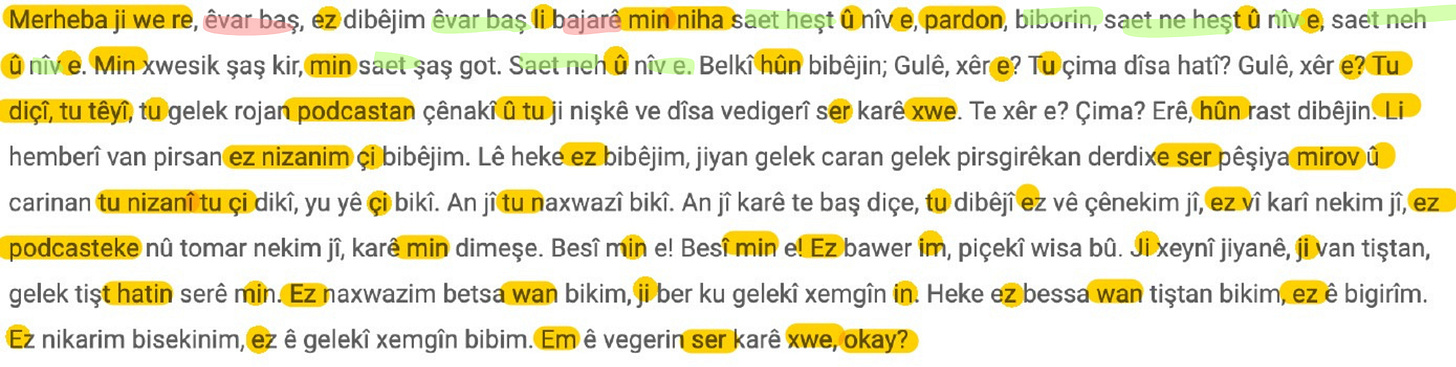

Here is the first paragraph of a text I set out to read last week, my first-ever text in Kurmanji. It’s a transcript of a podcast episode. The podcast tells stories in Kurmanji, but this is just introductory small talk. It’s the ideal learning material because it’s natural speech that I can both listen to it and read.

I’ve highlighted all the words I knew or could easily guess.

When I first met this text, I had only quickly skimmed through the first few pages of a reference grammar and I knew:

what sounds all the letters correspond to

All forms of personal pronouns in the nominative (the equivalent of “I”, “you”, “he”, “they”, etc.) and oblique (“me/my”, “your”, “his/him”, etc.) cases.

copulas (i.e. the different forms of the verb ‘to be’, like “am”, “are”, “is”….)

a few prepositions

how to form verbs in the present tense.

Someone else would look at this paragraph and get discouraged at how much work lies ahead.

I looked at this and got incredibly excited because oh my god look how many words I already understand after only 1.5 days with this language!

(Never mind that most of these words are “I”, “me” “of” “to” and “on” plus a bunch of loan words that give me very little information, like “pardon”, “podcastan” and “okay.”)

As you can see, this was not shaping up to be a relaxing reading experience.

Hardwon knowledge is retained better

When I read, I like to play this game: I pretend that for every word I look up, a bad person somewhere far away kicks a homeless kitten. But if I succeed in figuring out the general idea of the whole text, every homeless kitten on the planet will find her forever home. The goal is to get there while hurting as few kittens as possible.

Why do I do this?

We don’t need to understand every single word in a sentence. Even in your native language. Imagine you have a bad phone connection when talking to a distant friend so you miss a lot of words. You’ll still understand what your friend is saying even if you catch a few key words.

Because hardwon knowledge is retained better than spoon-fed knowledge. That applies both to words and grammatical patterns. If you figure out how to say something from the context (maybe through trial and error) rather than from a dictionary (or an app), or a grammar book, you’re more likely to retain that knowledge.

When you don’t look up every word, you send a signal to your brain that language is a means, not an end, that this language is a way for you to understand the world and interact with it. You’re not just an amateur word collector.

In other words, I have to be very selective about which words I look up.

In the first sentence, I can easily figure out the meaning of the first phrase, Merheba ji we re. Merheba is an obvious loanword from Arabic meaning “hello,” and ji we re means “to you” (we is “you” and ji…re means “to.”)

Beyond that, I know that ez means “I”, li means “on/in”, min means “my/me”, niha means “now”, û is “and” and e is “is.”

I decide to look up the phrase êvar baş and the word bajarê.

êvar baş means ‘good evening’ and bajar2 means “city” so li bajarê min means “in my city.”

I also know that dibêjim is a verb in the present tense but I decide to spare a kitten and don’t look it up. I figure she’s talking about the time of day (êvar baš li bajarê min niha “it’s a good evening in my city now”) so the verb probably isn’t important.

Knowing she’s talking about a time of day also helps me guess the meaning of the rest of the sentence, without hurting any kittens. In the phrase saet hešt û nîv e, the word saet is probably another loanword from Arabic meaning ‘hour’ or ‘time’ and hešt û nîv e (“X and SOMETHING”) must be the time. I don’t need to know what time it is but I can guess that hešt probably means ‘eight’ and neh later in the sentence probably means ‘nine’ (similar to English, because it’s an Indo-European language, remember?). I also don’t need to look up the word biborin: since it appears right after pardon, it is probably just another word for ‘I’m sorry.’ If I’m wrong and this word is frequent enough, I’ll have a chance to figure out the correct meaning later.

See? We’ve just figured out the meaning of an entire sentence, learned how to say ‘hello’, ‘good evening’, and ‘I’m sorry’, learned how to tell the time, learned that the possessive pronoun comes after the noun (‘my city’ is bajarê min NOT min bajarê). And only two kittens got kicked.

OK, I got lucky with this first sentence. Things got admittedly uglier later on.

In the second sentence, Min xwesik şaş kir, min saet şaş got, I already know two words: min ‘me/my/by me’ and saet ‘hour / time.’

I have a feeling that şaş is an adjective just because it looks like baş ‘good’ in êvar baş ‘good evening’ so I don’t look it up. Instead, I look up got and kir and find out that got means ‘said’ (past tense of ‘say’), and kir means ‘did’ (past tense of ‘do’.)

It’s not particularly helpful so I look up şaş. It means ‘wrong’ (an adjective, like I thought) but I still have no idea what the sentence Min saet şaş got means. The sequence of words “me/my - hour/time - wrong - said” doesn’t make a lot of sense…

Then I remember reading that in Kurmanji, the subject of transitive verb in past tense appears in oblique instead of nominative case. That is, you cannot say in this language “I saved the kitten” but only “The kitten was saved by me.” 3

So this sentence Min saet şaş got means “I said the time wrong” but translates literally as “The time was said wrong by me.”

Grammar is for linguists and nerds

It might take me a few hours to translate one paragraph like this. I might take a detour here and there whenever I feel like it — for example, to write my own sentences based on the ones I’ve just read, or to look up how past tense is formed in this language, or another grammatical pattern.

I do it because I like it, and because it speeds things up for me, but it is my conviction that if grammar makes you nervous you can totally skip it. I think it’s possible to learn to speak and read a language without ever consciously thinking about grammar. If you spend enough time with it (reading, listening and/or speaking if you’re lucky enough to be in an immersion environment), you will figure out how to use it and you will learn all the rules, unconsciously, just like children do.

By the time I finished translating this particular paragraph, I have

caused way too many kittens to be kicked4

learned how to form sentences in past tense and future tense

learned lots of new words

learned that Kurdish is a very idiomatic language. That means that a word in a sentence won’t necessarily mean what the dictionary tells you it means. It often combines with other words to mean something else entirely. Russian is a little bit like that I think. Sanskrit is very much like that.

decided that it’s not actually very interesting to read a transcription of someone’s introductory small talk and that I should have skipped to paragraph 4 where the story starts.

It took a lot to get there, look how many kittens have a loving home now.

If you’re a writer on Substack, consider recommending Friends with Words to your readers (go to Dashboard>Settings>Publication details>Recommend other publications on Substack). I’ve set out to learn 12 languages in 12 months and to share insights about language and learning along the way.

Friends with Words is the main thing I do this year. If you enjoyed this post, consider buying me a virtual coffee ☕☕☕ 😸 💜

Incidentally, Andrew Huberman says that cultivating a growth mindset lets you leverage dopamine dynamics and learn better.

I was wrong: Google Translate does have Kurmanji Kurdish. You have to be careful when consulting Google Translate. I double-check everything (e.g. I might do a reverse search, e.g. English-Kurdish to confirm, or do a general Google search.)

This phenomenon (called ergativity) exists in many other languages, and I’ve never particularly liked it, or understood it very well, but look I’ve already encountered it out in the wild!

No actual real-life kittens or other baby animals were hurt during the translation of this paragraph or the writing of this post.

You are a superhero (and a kitten-rescuing superhero at that)!

All this sounds very, very familiar! Reminds me of the time(s) I hit on a Wikipedia page where I can't even tell the language from its name :) I'm not sure why I don't do this more. But perhaps, with this as an inspiration ...