Friends with Words is a newsletter about language, culture, and identity, created by a Russian-born, Israel-based essayist, linguist, former world traveler, and single mom.

If you’re disillusioned by the current state of humanity, but still secretly hope that curiosity can fix the world or at least make it a less horrible place, this space is for you. Welcome.

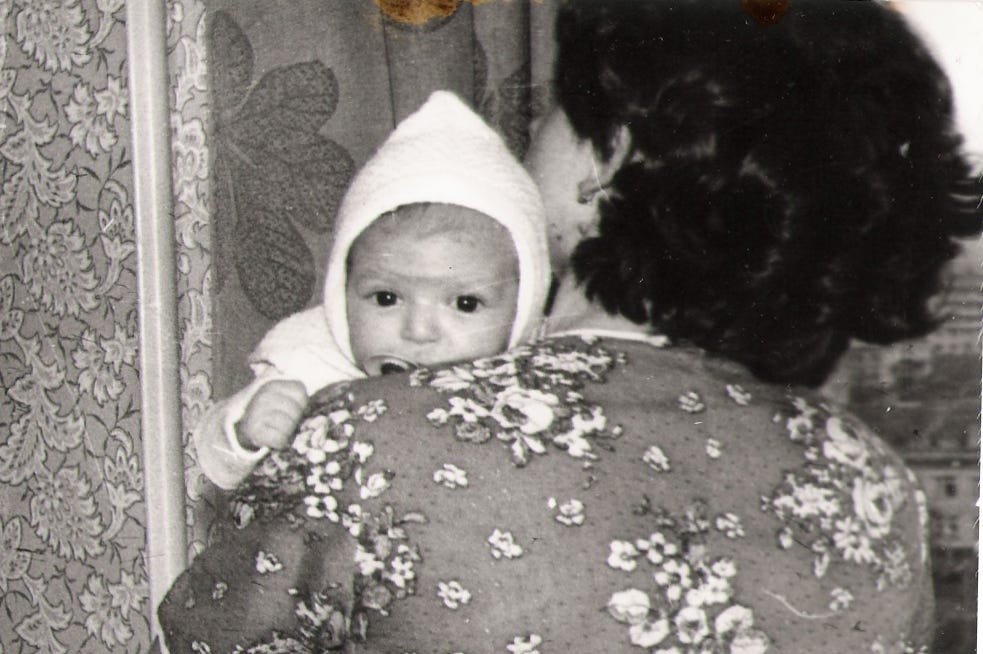

When I was about two years old at a big extended family gathering, I came up to the adults' table, approached my mom, and announced: Kayandasik v uske! which translates from baby Russian as "I have a pencil in my ear!"

They all looked into my ear and saw a tiny black dot — the mere tip of a pencil lead — lodged deep inside. All the adults proceeded to scream and/or flail their arms in horror and helplessness — all except for my mom. She calmly took a pair of tweezers and with steady hands pulled the lead out.

That's how it always was. My mom’s calm and steady 'It will be fine' was the backdrop of our family life. When my dad fell from a chair hanging curtains, broke the window, and cut an artery in his arm, she took a pair of stockings and tied them above the wound. When he hesitated about whether we should move to Israel, she was the optimistic force behind the decision. After the move, with barely any Hebrew, she found work, learned how to drive, and remained the adult in the room even after all her children became adults.

A year and a half ago, at not yet 75, my mom was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

The main reason we took her to the doctor was because she kept falling. She fell once, on her face, while taking a walk outside. Then on New Year's Eve, she left the house without her phone, abandoning boiling potatoes on the stove. We spent that night searching for her until we found her in an ER around midnight - a passerby had caught her falling and called an ambulance.

A week later I took her to the doctor.

She asked, “Why are we going?”

I said, “To check that everything is ok.”

“I’m ok.”

“I know. But you fell twice.”

I decided I would take her medical card and go in to talk to the doctor by myself first, to tell her things that I couldn't say in front of my mom. Already, that role reversal was disorienting. When I asked her to give me her medical card, she didn't protest, as if I were the adult now and she was the child.

I told the doctor about the New Year's Eve incident, about declining personal hygiene, her neglected apartment, and how she keeps searching for my father even though she knows he died three years earlier.

I thought she would prescribe antidepressants.

But when my mom came into the room, the Russian-speaking doctor started asking her questions that seemed to me completely unrelated to the situation. In a very loud voice (Why, doctor, why? She is not deaf! She is not even old!) she asked:

“Where do you live?”

She gave her address.

“What floor?”

“Third.”

“When did you make aliyah to Israel?”

“19….87”

My jaw dropped. She was off by 10 years. Maybe she misspoke.

“Where did you come from?”

“Kirishi.”

“Where??” the doctor grimaced. Nobody knows where the god-forsaken Kirishi is (we usually say we’re from St Petersburg, the closest big city), so I wanted to intervene to explain that she was correct, but the doctor subtly waved me away.

She continued: “Who did you come with?”

“My husband and my son.”

“And who is this?” she says, pointing at me.

“My daughter.”

She got confused about who came when, mixing up years and people. I kept trying to justify it all in my head — she forgot, she misspoke, she must be tired. But it was too late. The earth had already been swept from under my feet.

Since then, things have been rolling down the hill very quickly. Another doctor's appointment officially confirmed the diagnosis. Registration with the city's social services so she could go to the seniors' club for people with dementia. Soon it became clear she couldn’t be left alone, so we found a live-in carer. For a while, she could still do her daily tasks and handle personal care on her own, then gradually, she needed help with essentially everything.

I take a pencil out of my bag and ask her if she wants to draw. She nods. She barely speaks anymore (in any language), but she can nod yes or shake her head no. It takes her twenty minutes to draw a flower. She draws three petals and then stalls, drawing over the same petal over and over again, all while looking distractedly around the room, apparently not understanding that she needs to adjust the position of the pencil to draw the petals at the bottom. I rotate the page for her to finish (she doesn't seem to care, but I can't bear to look at that unfinished flower and that tortured last petal.)

A well-meaning friend asked how all that made me feel. But I can't even answer. I'm not numb, I'm exactly the opposite: I feel like a pot of boiling feelings, and I'm barely keeping the lid on.

Also, I can't allow myself to stop and reflect on how her state makes me feel anymore. Because every time in the last 18 months I allowed myself to dwell on my feelings of anger or sadness or resentment — "Oh no, all she wants to do now is color the mandalas like a five-year-old!" — I've been slapped in the face by yet another "new normal."

Now I miss the days when she sat in front of the TV all day and colored mandalas. Just like I miss the days when she ate and food fell out of her mouth because at least she was eating by herself.

This is our new normal. Except that it doesn't feel right to say even that. Because the phrase "new normal" implies you've arrived somewhere, and that things are gonna stay constant for a while, but in my mom's case, the only constant has been that her condition keeps getting worse at an astonishing pace.

So I say, this is our now.

I've long gotten used to the fact that she's not the adult in the room anymore. But the thought that I might have to be the one who holds everything together, the one taking the metaphorical pencil lead out of her ear — that thought still terrifies the hell out of me.

If you’re a writer on Substack, consider recommending Friends with Words to your readers (Go to Dashboard>Recommendations>Manage>Add recommendation)

Yes, we always think that our parents will be strong forever. It is hard to see their decline, no matter which form it takes. But neurodegenerative conditions hit particularly hard, in so many ways. Courage!

You're welcome, Tanya. I hope so, but in case it happens, if I HAVE TO figure it out, I know I WILL find a way to be "the adult in the room".

P. S.: Iranians have a personality trait, which i don't know how to translate it to English called "shekaste-nafsi", in which they give an unreal version of themselves for sympathy purposes. As much as i don't want to use it, i can't help myself. Sorry if i seem so.