Make a Fool of Yourself Friday - Issue #6

A special Monday edition

Dear language-speaking people,

Welcome to the special Monday edition of our Make a Fool of Yourself Friday series.

It is special because I couldn’t wait until Friday.

I mean, show me a guarantee that we will even have another Friday.

You can’t.

In that spirit, here is me telling you a story in a Mystery Language.

As always, the usual disclaimer applies: I'm not conversational in this mystery language, I just started learning it two days ago. I'm just saying things because it's fun.

As always, I’ll add a distracting picture after the story to give you a chance to guess what language it is or at least in what part of the world it is spoken. I've been working hard on my Mystery Language accent.

This was Maori, people. (Hopefully.) A Polynesian language spoken by the indigenous people of New Zealand.

The Why

Because I needed a break

I wanted a language that is spoken as far away as possible because this is the closest I can get to moving to a desert island.1 Learning Arabic has been magical in many ways that I'll tell you later about but at the same time it brought me a bit too close to our everyday reality here.

I think I was feeling guilty for running too far away from reality into other languages and not being here when my country needed me, and I thought Arabic would remedy that. It did, I don’t feel guilty anymore, I just feel overwhelmed with too much reality and need a break.

Ideally, I wanted a language that's spoken only by a handful of elders or one that has been dead for a generation or two, just to make sure that there is no chance that I'll ever meet a speaker of this language because language speakers tend to ruin languages (in all sorts of ways).

Maori is spoken by some 100,000 people which is too many for my taste but on the bright side that means it's easy enough to find resources online.

Because whales

On Thursday I went to Tel Aviv to meet a friend who I've known online for nine years but had never met in person. We met on the beach next to her hotel and talked while Maya played in knee-deep water (her first time on the beach this year). And then, a few hours after we left, only about 300 meters away from where my daughter splashed in the sea, a Houthi drone hit an apartment building in Tel Aviv and killed a sleeping person.

I read the news the next morning, then quickly opened another tab and learned that the Maori people have a very complex relationship with whales and felt that this was the sort of complexity that I desperately needed to know more about.

The How

How can you start speaking a language two days after you start learning it?

First of all, keep in mind that speaking is not the same as conversing.

Second of all, maybe that’s because the stakes are very low. I don’t actually want to become conversational in Maori, I just want to read a good story about whales in this language. With Arabic, for example, the stakes are higher because I want to be able to speak it at some point, which is why I’m not speaking yet. I wanna take my time.

I’m having a one-night stand with Maori, if you like, and so we can just fool around.

Third of all, you can start saying things in theory within the first 2 hours, but in practice you spend on average 1.5 days just looking for good resources.

Fourth of all, you avoid getting overwhelmed. You take only what you need at any given moment and you pretend, for the time being, that that’s all there is. You decide what you want to talk about and then learn only the bare basics of the grammar and the most relevant vocabulary for that first conversation with yourself.

The first thing I did was find out that:

Maori doesn’t have a very complicated phonology so learning how to pronounce new sounds is not going to slow me down.

It has a VSO (verb-subject-object) word order.

It’s an analytic language, meaning that words don’t change depending on their role in the sentence, so you can just go ahead and use the dictionary form of the word.

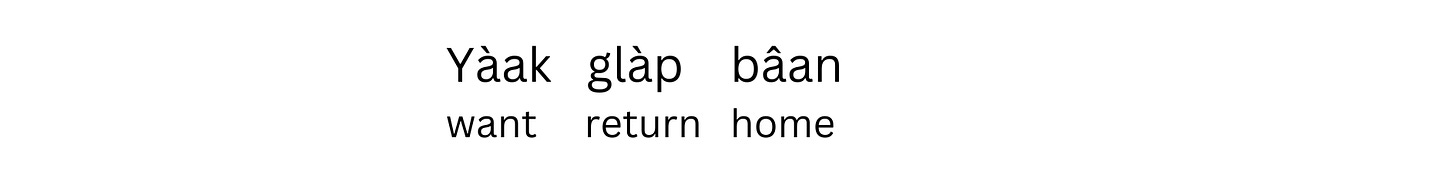

Unlike Thai, which is also an analytic language, in Maori, you have to use special particles that indicate grammatical categories like tense, number, etc. So, in Thai you can say the following three-word sentence:

…and it can mean “I want to go home”, “She wants to go home”, “They wanted to go home” or any other tense and pronoun, depending on the context.

But if you say the same three words in Maori (hiahia-hoki-kainga, ‘want-return-home’), nobody would understand you. You have to indicate who did the action and when.

To say “She/he will return home” you use the 3rd person pronoun ia and the special particle ka that indicates future:

If you want to change the tense and the subject (e.g. “I have returned home”) you have to indicate that change with special particles:

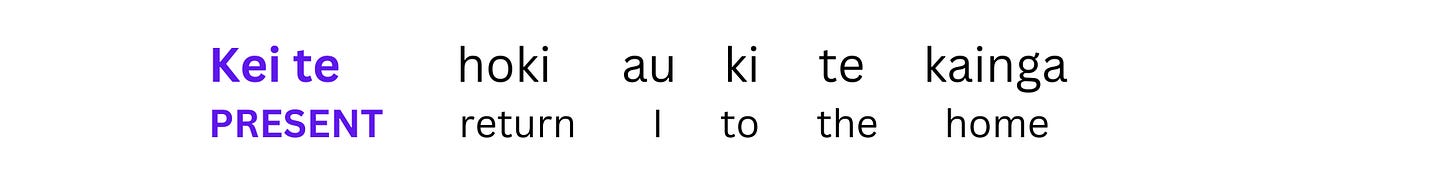

You even have to use a special particle for the present tense, which most languages don’t do. Here is how you would say “I am going back home”:

Why do some languages choose to mark all tenses, even present tense, with special morphemes / particles but others just leave you to figure it out from the context? Nobody knows. Languages do whatever they want. They’re cool like that.

I found this handy table showing all the tense markers. I didn’t have to, but I felt like committing the whole table to memory. So for a couple of hours, as I was browsing a hardware store for painting supplies (I need to paint my former study / laundry room pink and turn it into Maya’s room) and then dragging everything home on the bus in sweltering heat, I went around saying to myself, Kei te hoki au ki te kainga… Ka hoki au ki te kainga…. E hoki ana au ki te kainga….. (I go home, I will go home, I am going home….) and that’s how I learned all the tense markers. See? You just have to make it relevant to your life that’s all.

Then I picked some more useful verbs from this online dictionary. (‘walk’ haere, ‘speak’ kōrero, ‘live in’ noho, ako ‘learn’), and some nouns that I thought I might need (pukapuka ‘book’, rūma ‘room’, tamariki ‘children,’ tamāhine ‘daugher’, tama ‘son’ ), found out that nouns have to be preceded by an article (te for singular, nga for plural), and that direct objects also need a special particle i before them, and …. and voila! I could now tape the plastic to the baseboards while saying sentences with direct objects:

Ka rīti au i te pukapuka…. (‘I will read a book’)… Kei te ako au i te reo Māori…. (‘I am learning Māori’)…. Kei te peita au i te ruma (‘I’m painting the room’)…..

Then I decided that I was ready to learn how to use sentences with two verbs that have the same subject (e.g. I want to read…. I decided to paint)….and how to say complex sentences with ‘because’ because I wanted to explain to you guys in that video why I’m learning Maori (no te mea he hikaka ‘because it’s exciting) and why I’m painting the room (no te mea ka noho taku tamāhine ki tenei rūma ‘because my daughter will live in that room’2).

As you see I know very little Māori. I am aware of some other grammatical features that it has that I don’t know how to use yet, but that’s ok for now. You only need the bare basics to start speaking. It’s kind of an exciting challenge actually to be able to say what you need to say with very limited vocabulary and grammar.

My next challenge is to be able to say Kua peita ahau i te rūma, ‘I have painted the room’ and for it to be true.

But that’s a whole other challenge.

If you’re a writer on Substack, consider recommending Friends with Words to your readers (go to Dashboard>Settings>Publication details>Recommend other publications on Substack). I’ve set out to paint one room and learn 12 languages in 12 months to inspire people to do what they want to do while procrastinating on what they have to do.

I'm aware that New Zealand is not a desert island. I have a friend who lives there, so that makes it at least one person. But from where I stand it's easy enough (and very comforting) to pretend that it could be.

I don’t know yet how to say ‘I promised her’ and ‘She’ll kill me if the room is not done by the end of August’ but see? I still managed to convey the general idea even without these very important sentences!

Fascinating❣️ I loved reading this.