In the fifth grade of our Soviet school, we started learning English.

At that time, the USSR had only one state-approved textbook of the English language. It had grainy pages and black-and-white illustrations, and it followed the pursuits of a fictional Soviet girl named Lena Stogov and her brother Boris Stogov.

All soviet children from Uzbekistan to Chukotka had to learn the language of Shakespeare and Lemony Snicket1 by reading about Lena and Boris Stogovs’ everyday business of being good Young Pioneers.

Here is one page from it:

Here is another (forgive the screenshot quality, I found these online):

These textbooks accompanied us from grade 5, and I’m guessing, until the end of high school (thankfully I left the country before Boris Stogov became a Komsomol member).

Things got marginally better after I moved to Israel. The good news is that we were now free from the Stogov family.

The bad news is that our English teacher in my high school in Israel was a native Romanian speaker who immigrated to Israel 20 years prior and must have been nostalgic for the good old Soviet times.

We never had a chance to find out how much English she knew, because every time she saw us she seized the opportunity to recite Soviet-era poems in Russian that she must have learned as a child back in Romania:

Utro krasit nezhnym svetom

Steny drevnevo Kremlya….

(“The morning is painting with tender light

The walls of the ancient Kremlin….”)

It must have been fun for her to practice her Russian with us, but it was neither fun nor educational for us, kids who’d just left the former Soviet Union and weren’t yet nostalgic for everything Soviet.

Then came another teacher who had us read a play by Arthur Miller called “All My Sons.” I have no memory of what the play was about, but I do remember being bored out of my wits (no offense to any Arthur Miller fans out there, I’m sure he is great and I just wasn’t mature enough to appreciate him.)

In other words, my education tried very hard and almost succeeded in squashing my chances to learn English.

I only properly learned it when I finished high school, moved in with my parents, and started watching English-language movies with Hebrew subtitles.

Back in the Soviet Union, education was incompatible with ‘fun’. If you were having fun you couldn’t be learning. But at least that was consistent with the general ideology. ‘Fun’ or ‘Enjoyment’ didn’t exist as categories in any aspect of the soviet experience.

They do exist in the modern world, which makes it all the more mysterious why so little effort is put into making learning enjoyable (and relevant) for people of all ages.

After two years of French in his British primary school, Yannai came home and uttered his first full sentence in this language. He said: Je veux aller en Australie et voir un ovni. “I want to go to Australia and see a UFO.”

Kids are capable of a lot more than that. Just saying.

Or the English classes at Maya’s school. They have them do flashcards.

At least in English and French, there is a variety of resources out there (you just have to make an effort to find them.) The problem with lesser-known languages is that often there is not much to choose from.

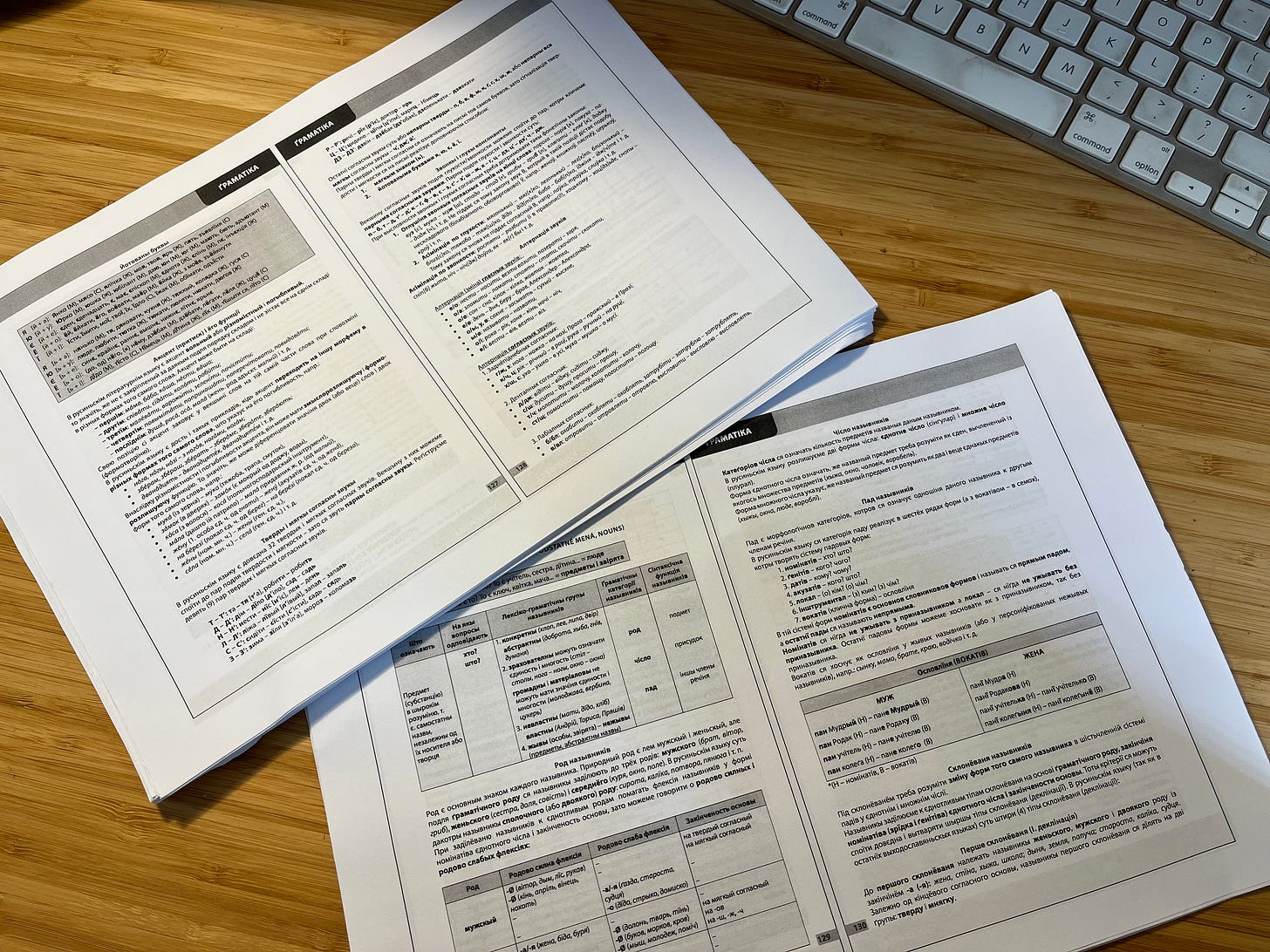

At the beginning of this year, when I set out to learn Rusyn, I found only one resource online. This textbook:

I was able to get as far as the table of contents. It has no pictures, no colors, and no interesting stories. I already had trouble learning this language. It’s an East Slavic language that’s very close to Ukrainian and Russian that was strategically chosen to make my language-learning life easier. But it turns out that it’s much harder to learn a language that’s very close to your own. I didn’t even know where to start.

And this textbook didn’t help my motivation.

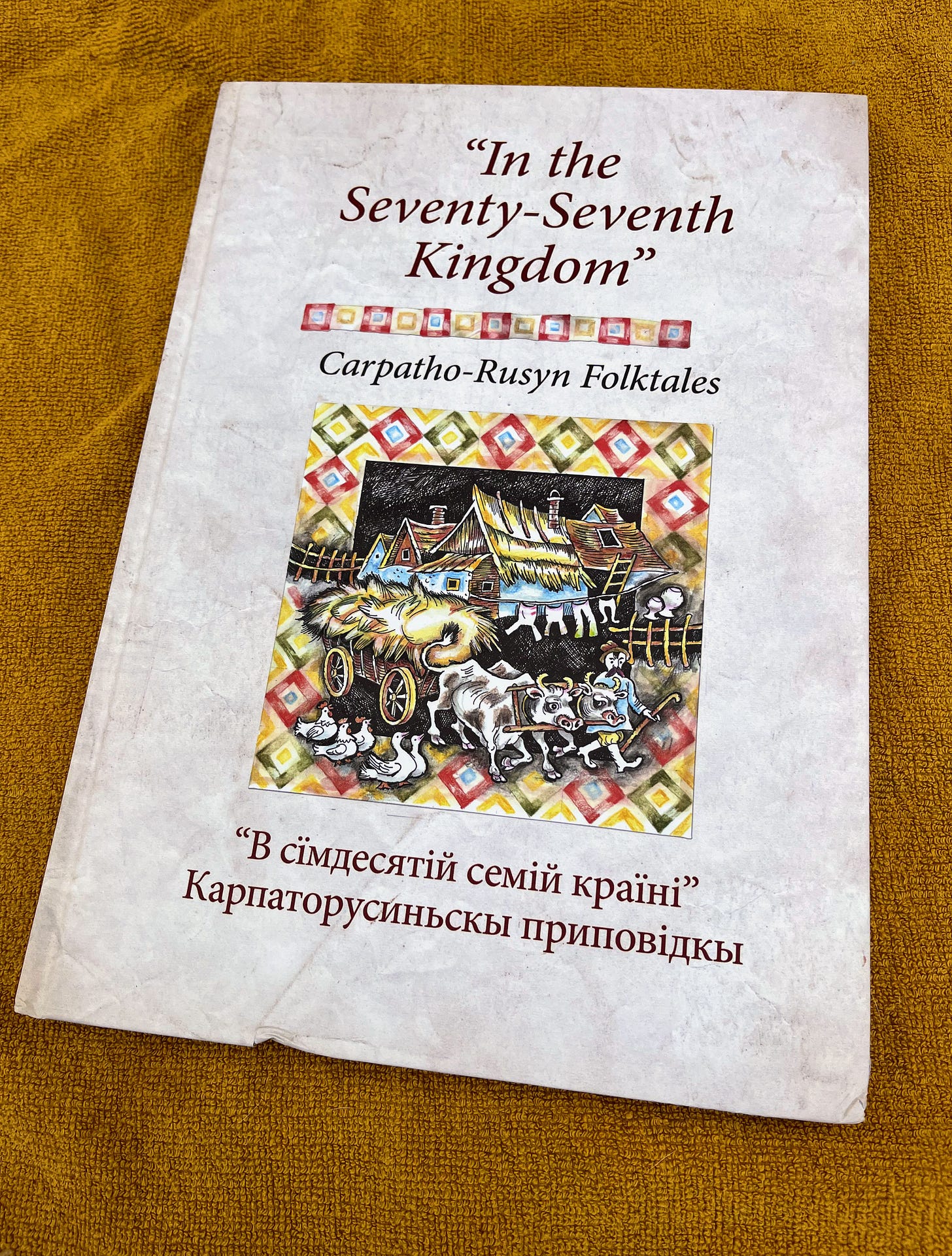

I knew what I wanted. I wanted to get my hands on a beautiful bilingual illustrated book of Rusyn folktales that I’d found online. This one:

But I couldn’t get it because it was produced and distributed only by the Carpatho-Rusyn Research Center in the States, and the shipment from there to Israel cost more than the book.

After scouring the internet and making sure the book wasn’t sold anywhere else, I emailed Prof. Paul Magocsi, the founder of the research center who worked at the University of Toronto (and whose name rang familiar from my years there), and asked him if there was any way someone could mail me the book. He replied the same day, saying he might be able to help, and asked for my address.

I didn’t have much hope. Because of the war mail doesn’t get here very regularly.

But last week I got a package in the mail addressed to Dr Tanya Mozias Slavin. Nobody sends packages to Dr Tanya Mozias Slavin because that’s not how I introduce myself on Aliexpress and other e-commerce websites.

It was my very own beautiful book of Rusyn folktales. Courtesy of Prof. Magocsi. Yay.

Because it’s bilingual in English and Rusyn (and because I know Russian), I understand about 80% of each story, but now I’m actually motivated enough to figure out the differences between Russian and Rusyn which will help me understand the remaining 20%.

Most importantly, it’s a feast for my eyes and my brain and my soul.

Look at this:

There is a scientific basis to the idea that to be effective, learning has to be fun. Or, to put it in academic terms, cognitive engagement (i.e. our ability to engage effectively in learning) relies heavily on emotional engagement.

Not that you need to conduct controlled studies to confirm the very intuitive idea that we’re much more likely to learn something if we’re enjoying the process. But maybe it was worth losing an hour to ScienceDirect.com if only to find this study from 2023 where participants were asked to wear a device that measures exactly just how much fun they’re having while learning something.

(Also that article’s opening sentence is a real gem. It claims that “emotions are something almost everyone feels and expresses every day.”)

Is the world getting more absurd by day or is it just that when you combine academics, emotions, and wearables, things automatically get ridiculous?

By the way, emotional engagement can mean several different things:

you love the learning materials or the topic (e.g. I love folktales)

your learning process comes with a feeling of belonging (E.g. “I don’t like math but I love my math teacher so I’m actually learning something.”)

something else (e.g. “I couldn’t care less about languages but I enjoy reading about Tanya’s dog swallowing socks so much that I keep reading “Friends with Words” and learning stuff despite my best intentions.”)

I love folktales because I find there is something pure and real in myths and folktales of any culture. I also have a special relationship with Slavic folklore. Maybe it’s because I grew up reading Russian folktales. Or maybe when I was little my father was writing a dissertation in ethnomusicology, so I’d play hide-and-seek to the sound of Russian grandmas singing from his tapes in the kitchen.

Of course, we all enjoy different things.

Maybe you don’t care about folktales but like listening to news or weather reports, or reading vampire romance novels, or watching soap operas. The idea is to find something that’s uniquely you, that makes you go oooh that’s so cool, that motivates you to learn, and lets you enjoy the learning process in a way that can’t measured in streaks or gems or hearts or XPs (or maybe even a wearable device.)

Sadly, we’ve learned to settle for these other cheaper versions of fun, but I’m not at all sure it’s good for our soul or our learning process in the long term.

Lemony Snicket hadn’t yet written anything in 1993 but I’m still upset because if he had, I’m sure we wouldn’t be allowed to read it.

I love this illustration of The Fox and the Wolf. (I’m curious about this folktale as well!) Thanks, btw, for sharing this. It’s an important reminder for both teachers as well as students… It wasn’t until I completely changed my approach to learning French (after years of stop-start efforts in school) that it became fun and I actually started making progress. Podcasts, movies, 1:1 instruction, fiction, etc… Now I’m setting out on Italian, using those same fun strategies.

So glad you got your hands on that book of folktales! I love a good folktale myself.

Your story about your Romanian teacher reminded me of my French teacher. She was native Russian (born and raised) and was teaching our university French class. If someone got the answer wrong she’d pretend to shoot them with her finger-gun. Needless to say, I believe she had a meeting with our head of the department.