I've always thought that to remember something better, you have to write it down.

There is even mounting evidence that writing things down by hand is particularly helpful when it comes to retaining information (as

explores at Everything is Amazing.)I am a super visual person. I remember how things look, their color, and their location on the page. I am so intensely visual that I've always seen days of the week, months, and some numbers in color in my head. (I was convinced that everyone does that and only recently found out that not everyone’s Sunday is bright purple, and now I’m in awe of people’s ability to distinguish days of the week without painting them first.) In other words, I can’t imagine learning something without first visualizing it.

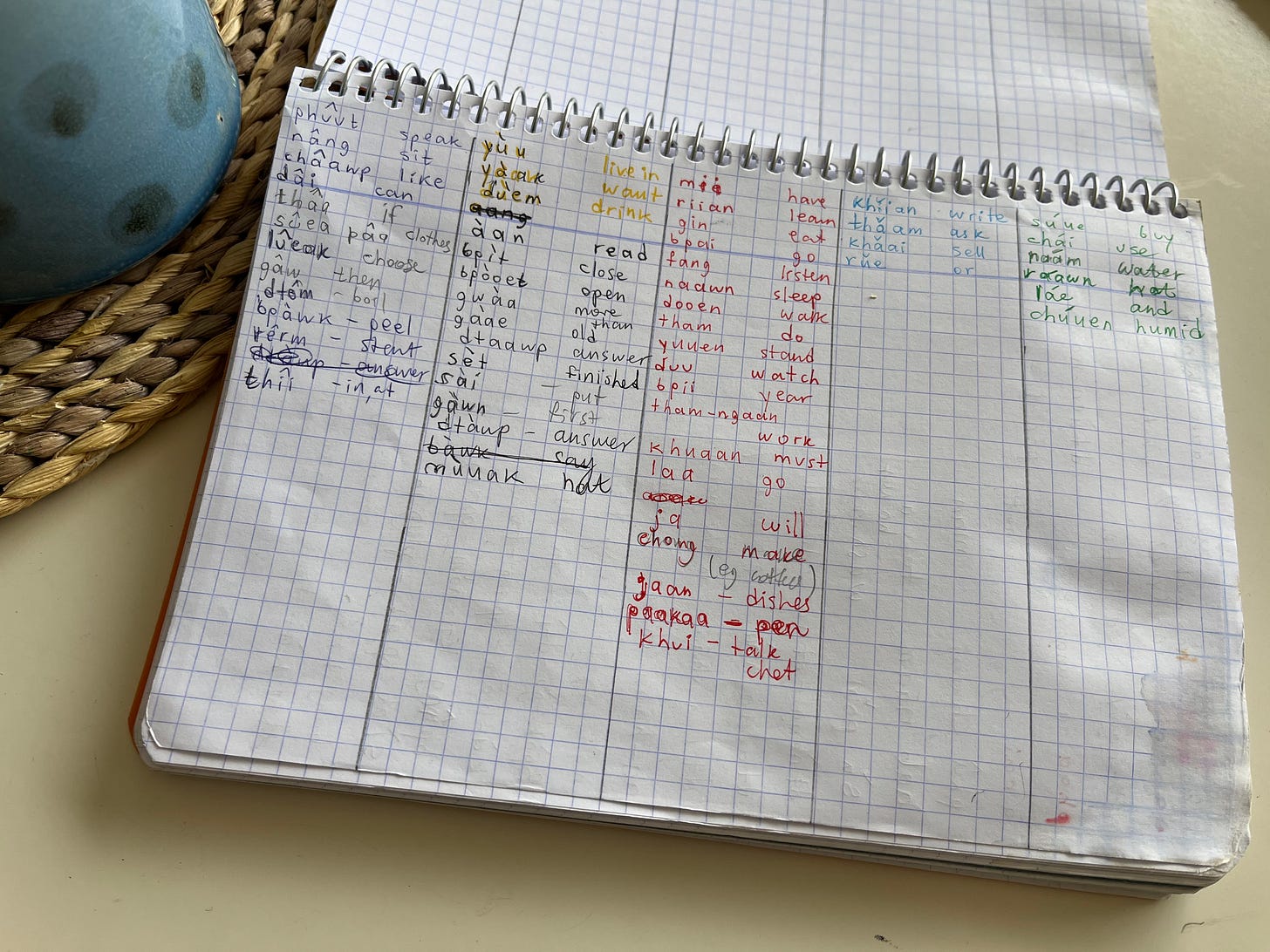

Until not so long ago, I used to write words down in tiny letters in a special notebook and say ‘Please, brain, please just these tiny words, they won't take up too much space on our hard drive, will they?’

Increasingly I have less and less time to do that because I don't have the luxury of learning just one language at a time, but somewhere at the back of my mind I still thought of it as the ideal I should strive for.

To be clear, I don't think memorizing random words is a good idea. But if you’re immersed in the same context for a while (say you’re watching a British series about a pig family), then it might be helpful to write down words you encounter frequently and review them from time to time. (Maybe. I’m not even sure anymore. I just like colored pens, ok?)

And then I noticed something strange. When recording the first MFYF video, I had only been studying Thai for two weeks, and it was still hard to memorize words with their tones (it’s gotten easier now) and since many words there were new to me, I thought I'd write everything down.

But a strange thing happened. The minute I wrote those words down, keeping them in my head became harder. It's almost like my brain decided, OK they're on a piece of paper now, and in front of my eyes, so we don't need to make an effort to remember them.

Now I always hold words in my head, even if they're new, regardless of whether I'm talking to myself or the MFYF camera.

I realized that in the last MFYF video, I look like I'm peeking at a piece of paper, so I want to set the record straight (because otherwise, of course, the internet police will be after me because look she's not really learning all these languages, she’s just reading and anybody can do that), and confirm that I'm not in fact reading. That’s just how my eyes work when I don’t make enough effort to reign them in (and I was sick so all my energy was directed at trying not to cough at the 2.3 million viewers that will be watching this clip in the years to come.)

In other words, paradoxically, even though writing things down has been proven to help you memorize them, it also somehow makes words fall out of your head.

Then I discovered Language Transfer. It is a language learning method developed by Mihalis Eleftheriou that is essentially an audio course based on a dialogue between the teacher and the student. The teacher leads the student through the grammar (in my case Swahili) starting with the basics, while keeping linguistic terminology to the bare minimum.

It is based on a much older method, developed by a guy named Michel Thomas (hat tip to

from Babel Babble where I first read about it) which is how people learned languages way before companies started competing for our eyeball time so they could sell our attention to advertisers.I had to step over some linguist’s pride to get into it. First of all, I don’t like a lot of hand-holding. I like to gobble up the basics of grammar as quickly as possible and then fill in the gaps by listening, watching, and reading. This language learning strategy is called “Throw Spaghetti at the Wall.” (Let’s, see, I might even trademark it.) Second of all, I don’t need somebody to explain to me what a noun is. Third of all, I don’t have time for a whole audio course consisting of 110 7-10 minute audio lessons.

But it was the only Swahili resource out there (not counting Duolingo because I’m not a fan) so I decided to give it a try.

And you know what? I kinda like it.

Right off the bat, Mihalis says not to write anything down. He says, confirming my intuition, that when you externalize the information by writing it down, you create a ‘second brain’ for storing this information and we want to keep what we’ve learned in our actual brain.

I already didn’t have time to write things down, but still, if Mihalis hadn't said that explicitly, I'd probably be stealing moments throughout my day to greedily collect Swahili words in a little notebook, worried that I'd lose them otherwise.

Giving up writing was a bit like giving up training wheels when learning to ride a bike but I’m proud to say that as of now I have not written a single Swahili word down1 and somehow magically my brain remembers most of them.

I emailed Mihalis and asked him how it works, and he said that he didn’t know either except that he knows that it works. He considers himself anti-academic and has never read a book about language teaching in his life. One day I'm gonna interview him so I can bug him some more about it, but for now, all I can offer is my thoughts on why I think it works so well.

Because the truth is that just not writing things down by itself is probably not enough. ThaiPod101 is also an audio course but all it did was annoy me with its business-related vocabulary and condescending dialogues.

Mihalis breaks the language down into tiny manageable chunks starting with the most useful things. You start by learning the most common verbs like ‘want’, ‘do’, ‘eat’, ‘sleep’, ‘like’, and practicing saying simple sentences like ‘I want to eat,’ ‘He is sleeping,’ ‘I like them’… which covers pretty much 45% of what we talk about every day.

He recognizes our brain’s inability to remember random information and does a great job helping you make connections. For example, if two words or two morphemes (parts of words) sound similar (e.g. kutaka ‘to want’ and kutoka ‘to be from’) he introduces them side by side and points your attention to the similarity.

He makes a good strategic use of repetition. You hear words from the previous lessons over and over again, learning to use them in progressively more complicated contexts.

He calls it “The Thinking Method” and I think it lives up to its name. Instead of telling you how things work, he often asks the learner to try and figure out what the right answer might be, based on what she already knows. Have you ever had this experience where you sit down very helpfully next to your kid to help her with her homework (maybe because she had trouble with question 4a) and the minute you sit down things start going downhill? Now she suddenly has no idea how to answer any of the questions, seems to have forgotten how to write, read, and count, and is on the verge of a meltdown? Then you get up to clean dog vomit off the living room carpet, and the next thing you know is that she’s figured it all out all on her own. Because when somebody is there to spoonfeed us the information, our brains are less likely to make the effort to find the solution. And if we found the solution ourselves, we’re more likely to remember it. This seems intuitively right, and if there are neuroscientists in the audience, I’d love for you to point me to relevant studies because I couldn’t find any. (I want to say I’m anti-academic like Mihalis because it sounds cool but that would be a lie.)

All of it points to the fact that memory works very differently when it comes to language learning, compared to, say, learning history or even remembering to buy milk.

Learning a language is more like learning a skill rather than storing information. If I’m learning how to ride a bike, it’s not going to help me to write down the steps of how to do it. I just need to do it. It’s muscle memory.

And then there are some wonderful side effects of this type of learning:

Thanks to Mihalis and his audio course, I’ve cleaned my entire apartment and got reacquainted with some of its distant corners that I'd forgotten even existed.

I can now wash the dishes, walk the dog, and watch Maya's flutter kick at her swimming lesson without blinking like she wants me to, all while learning Swahili.

I've discovered this bush that started growing on the couch on my balcony:

Now nobody can tell me that I'm bad at taking care of plants. They even grow in my furniture.

Please let me know in the comments:

Do words sometimes fall out of your head the minute you write them down?

What color is your Monday?

Do you also grow greens in your furniture?

Ok, maybe one eleven.

This language learning strategy is called “Throw Spaghetti at the Wall.” LOL.

Tanya I was practicing my Spanish the other day and had a literal WALL OF WORDS that I needed to commit to memory on a sheet of paper in front of me. I actually started looking at the word origins of each word to see whether I might be able to "make connections" like Mihalis suggested above. It actually worked pretty well. There were some word roots and origins where I was like "OH, that makes a lot of sense." It made learning these words so much easier. IDK how much this might help with Thai (probably not at all), but perhaps it might help you here and there.

Tan’ka! It is amazing how timely this essay has come out for me! I am going to hang that piece about spoon feeding our brain on the wall and read it every day ( being currently preoccupied with preventing brain drain in the future… well , you know why😔)

Being also a visual person, I am also very audio- (how do you call it ?) I perceive information by hearing it really well.

My Monday does not have a color, but it has an unmovable location , like in of our Soviet school agenda, if you remember:)

And, if I am not mistaken, that couch plant of yours was photographed by my phone so where is the credit?😉😂)